Latitude Sauna – A Reflection on Architectural Design and Confinement

by Nina Edwards Anker

In this time of Corona crisis, we need to press the reset button on the way we think of our roles as designers. How do we reframe our perspectives to enable us to see a wider angle, a ‘bigger picture’?” In spatial terms, as we zoom out from the narrow path, from the enclosed cave space to a wider lighter perspective, we may ask the following questions: how has narrow close-mindedness contributed to this crisis? How can we help to reframe the view as professional designers – can our designs help us to see a ‘bigger picture?’

Moreover, how can this period in quarantine serve us, as we reflect upon urgent issues while locked down in tight interior spaces? Perhaps we become more creative with time on our hands to sketch, read and address the phenomenon of claustrophobia or ‘cabin fever’ and its negative connotations, not to mention its detrimental implications on mental health. Our leaders have been building walls of different types – walls of ignorance in the face of scientific facts, walls of petty-minded racism, etc., which have led us to this global crisis. Are there ways in which designers can think in spatial terms about opening up these walls? In pondering today’s problems while quarantining or staying home, some of us in squeezed apartment spaces, for an unsettlingly indeterminate length of time, we designers may turn to the work in the 1970s of American architect Charles Moore’s concept of the ‘aedicule.’

In ancient Roman religion, an aedicula, diminutive of the Latin aedes, a temple building, is a small shrine. The word aedicula translates into English as “aedicule” or “edicule.” For Charles Moore, the aedicule was meant as the restricted place of reverie, whether awake in front of the fire, or in a half-slumber in bed. It was an architectural translation of Bachelard’s claim that bodily confinement forced people to experience “concentrated wandering,” to feel as though they were “elsewhere.”

“Latitude Sauna – A Reflection on Architectural Design and Confinement”

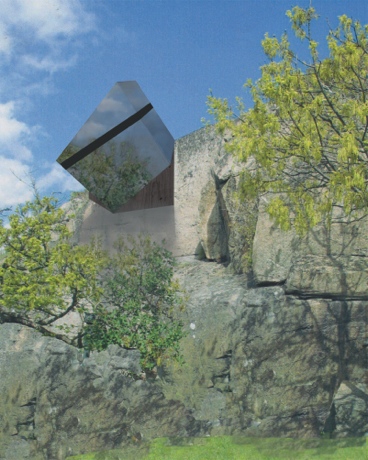

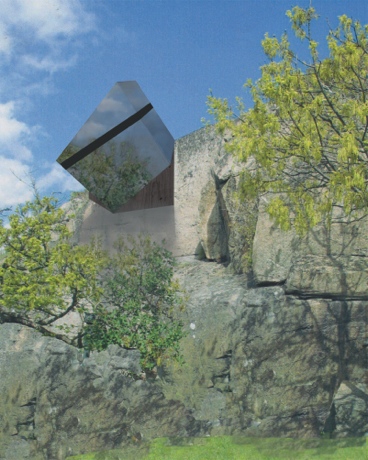

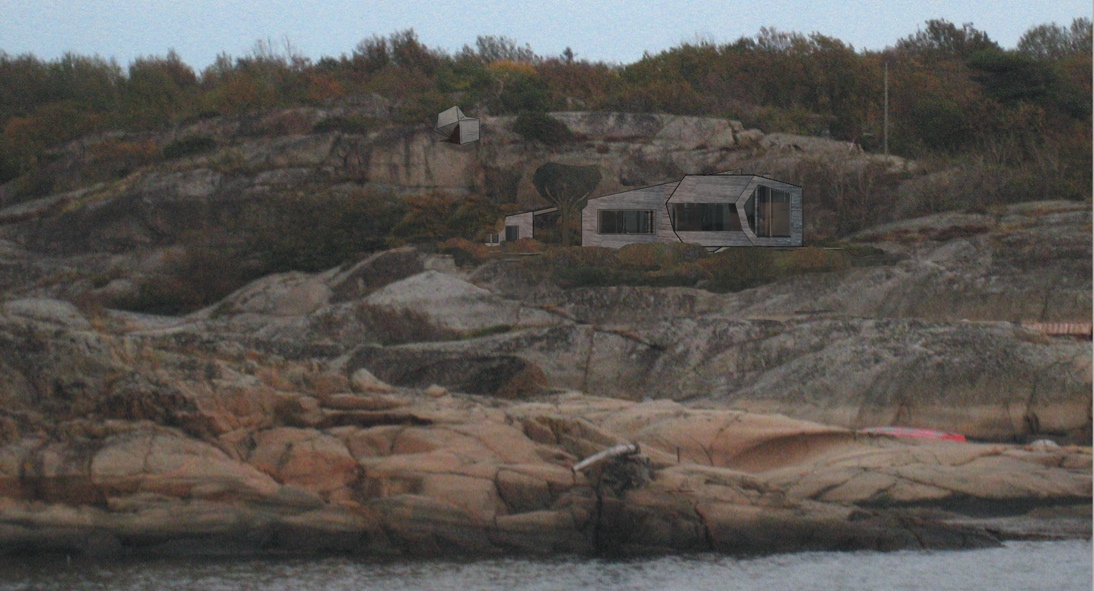

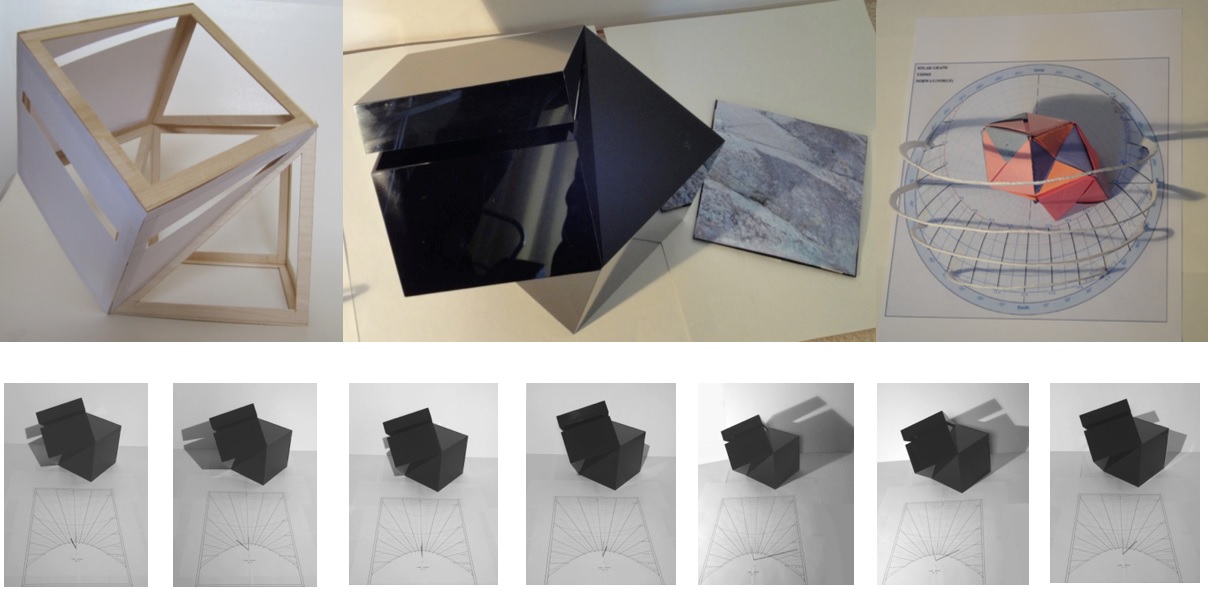

Latitude Sauna revolves mainly around the issue of scale, or the sense of expansion and contraction that it affords. The interlocking cubes of the Latitude Light series become inhabitable in the form of a sauna built into a cliff by a fjord in Tjome, Norway. The structure’s southern face consists of a large black semi-opaque photovoltaic panel angled sixty degrees for Tjome latitude. The amorphous thin-film panel mirrors the surroundings while filtering the sun’s entry into the sauna. A thin slit running across its three upward-tilting faces represents the local sun path from east to west.

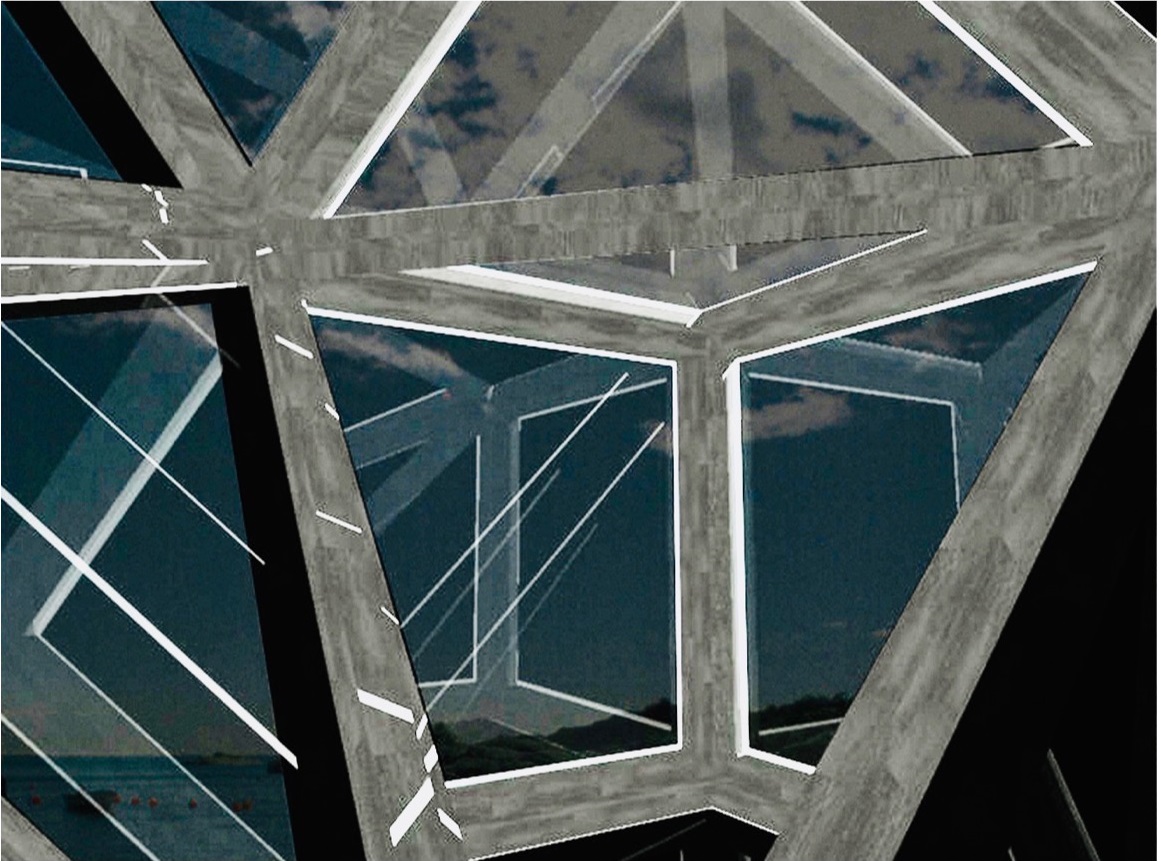

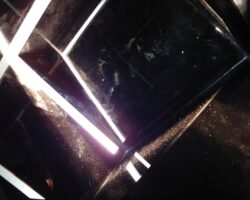

3.4.6. The PV panel mediates light inside the structure, a device for creating abstract light patterns

Perception of time also comes to the fore in the way the structure is carved into the cliff, its geological strata and curves shaped over time by wind and water. This ancient ‘svalbard’ rock contrasts with the new technology of the PV panel, its mirrored surface reflecting moving images of the present moment. The linear transparent window that cuts along its faces allows moving light strips to enter inside the dark structure, creating abstract line patterns on the walls and floor (3.4.6). The passage of sunlight throughout the sauna also marks cultural rhythms: one of the hands of the clock alights a steel blade in the sauna floor annualy at midnight on June twenty-third, marking the Norwegian mid-summer white night.

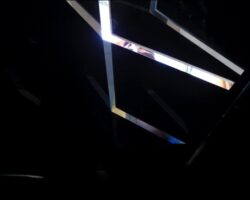

The semi-opaque solar panel veils outward views (3.4.3), allowing the visitor to focus on associated perception of time, as well as sensual perception of touch, smell, taste and sound. Inspired by Lisa Heschong’s book Thermal Delight in Architecture, the sauna aims to create maximum thermal ‘delight’ by stimulating multiple senses in addition to temperature. The sound of wind and the offering of cool local Farris spring water from the outdoor shower, which engages tongue and taste, correspond with cold or cooling breezes; the sound of water poured on the coals and sizzling into hot steam corresponds with intense heat. The smooth warm interior wooden planks contrast with the textured cold surface of rock outside.

Tactility and sound are among other senses that contribute to sense of scale in the experience of contraction and expansion in this little sauna on a vast open cliff. Sensual contrasts underline understanding of scale, where a tight sheltered space offers relief from the open wind-swept landscape. Light strips alight the rock, giving the feeling of being inside a cave (3.4.6). Upon entering and exiting the sauna, fresh smells of the garden contrast with the musty smell of rock and burning coals. The sauna offers silence and protection from the often-loud whistling wind.

The structure is designed in such a way as to foster interdependencies between scales. The experience inside the sauna is similar in some ways to that of a pilot’s experience inside the small cockpit of a Spitfire plane, as described by architectural historian Robert Kronenburg. In his discussion of humanistic associations with machines in Spirit of the Machine, Kronenburg quotes pilot Carolyn Grace, whose affection for the wartime Supermarine Spitfire Mk IX that she owns and flies is due in great part to multi-sensual stimulation it grants her, including forceful sense of scale, starting at body scale:

Every time I see the Spitfire it thrills me, it’s such a beautiful thing. When you climb up on the wing and slide the canopy open you get this wonderful, seasoned smell, a mixture of aviation fuel, hydraulic fluid and oiled metal. The cockpit is very narrow, and when you climb in, it sort of encases you within it. It’s a very secure feeling. I’ve met many wartime pilots who describe the same feeling – of becoming one with the airplane.[1]

The contrast between the tight squeeze of the body inside the narrow cockpit, enabling a sense of security, along with the vertical distance from the earth, allowing a sense of freedom, creates a powerful merging of bodily and global scale perceptions. It is partly through associated sense of scale that the Spitfire gains its powers of affectivity. The plane has such great ability to provoke sensual stimulation of smell, sight and tactility, along with associated sense of scale, that Grace not only desires to be in close proximity with it, she feels at one with it. Like the spitfire, the sauna is a tight enclosed space of sensual stimulation that contrasts with the infinite distance to the horizon viewed from its window.

Charles Moore has created intimate spaces with a similar focus on multi-sensual experience of natural elements, called “aedicules.”[2] Inspired by Gaston Bachelard, Moore’s spaces are often designed around the sensual apprehension of the four elements, earth, air, water and fire, in connection with reverie. Latitude Sauna shares this intention:

The aedicule was meant as the restricted place of reverie, whether awake in front of the fire, or in a half-slumber in bed. It was an architectural translation of Bachelard’s claim that bodily confinement forced people to experience “concentrated wandering,” to feel as though they were “elsewhere.”[3]

The sauna belongs to a particular type of architecture, which, because of its tiny size, can be all the more powerful in its expression of the global. Other artists and architects such as Charles Moore and James Turell have worked with this genre as a way of expressing a forceful sense of contraction and expansion.

The sauna, while focusing on personal perception as Moore does in his aedicule designs, also aims to raise awareness of surrounding community from the ‘glocal’ perspective. The parametrically adapting shape, the embodiment of the local sun passage in the form of the window strip, and the steel blade lighting up according to the yearly cultural ritual of midsummer night festivities, all point to an appreciation of the presence of the sun as a force that contributes to a larger perspective beyond the personal. These design moves commit to an acknowledgment of the role of today’s designer to address the global perspective and embrace local traditions. The role of the architect has changed since the ‘Me‘ era of 1970’s liberation in which Moore operated.

In this design, sense of place and sense of material mutually reinforce one another. The sauna will reflect local context in its mirrored PV panel and blend in color with its grey cliff backdrop. The locally sourced wooden slats on the sauna’s facades and the cliff are complimentary weathered textured surfaces.

Rather than blasting a hole into the cliff, the structure is to be carefully tucked into its existing dimensions and topography. After extensive measuring and recording of the cliff’s existing topography, Latitude Sauna is to be inserted into it so that its back wall and base rest into and upon the weathered surfaces of the rock. The sauna lightly rests within the natural patterns of the ancient rock’s geological strata, which have been shaped by the elements throughout the years.

The amorphous thin film face of the sauna serves to mediate the larger surrounding geographical elements into a confined space. Because the views from within the sauna are semi-hidden, the visitor’s vision becomes hazed, encouraging focus on the other senses. At the same time, the slit in its surface allows for strips of moving light that starkly contrast with the dim interior, heightening awareness of the passage of the sun, potentially creating a new “grammatology of light” inspired by artists like Moholy-Nagy.[4]

The primary aim of many present-day artists and designers, like Moholy-Nagy, is to create dynamic light conditions in their works. Dynamic natural light conditions can convey a sense of awareness of planetary processes, as they do in the projects by American artist James Turrell (born 1943). The ultimate artist of natural light conduction, Turrell speaks in an interview about our present-day state of connection with the earth and the cosmos. Turrell believes that ancient civilizations of Christians, Mayans, and Egyptians, whose calendars were linked to movements and positions of the planets, were endowed with a connection with earth and sky that we have now lost. Turrell explains how in his work he attempts to raise awareness of the movement of the stars and sun:

To feel that we are in any way apart from nature is our greatest conceit. And after experiencing tsunamis, hurricanes, earthquakes and volcanic lahars, not to mention the effects of global warming, we’re occasionally reminded of nature’s presence. It is my hope to have a work that in some small way reconnects us with our true nature by gently investigating the nature of perception within the so-called ‘nature’ that is outside us.[5]

In the all-important aim for artists, architects and designers of the 21st century to bring humans and planet closer together, the skillful conduction of natural light becomes an essential tool. Latitude Sauna is designed to foster interdependencies between scales, especially the scale of the human being with the “’nature’ outside”. In its constricted, dark and overheated space, the sauna arouses heightened sensory perception of the vast nature outside.

[1] Robert Kronenburg, Spirit of the Machine – Technology as an Inspiration in Architectural Design, (Great Britain: Wiley-Academy, 2001), 62

[2] Jorge Otero-Pailos discusses Moore’s “aedicule” designs, small semi-enclosed spaces in which the four elements of the material imagination, through means such as skylights, baths and fireplaces, play a central role (Moore’s aedicules are discussed earlier in the section on Solar Calendar): “The aedicule’s intimate interior was conceived as a device for training the senses to achieve controlled introspection and self-discovery. The aedicule was meant to assist the architect-historian to experience his creative self.” Jorge Otero-Pailos, Architecture’s Historical Turn – Phenomenology and the Rise of the Postmodern, (Minneapolis: Univ. of Minnesota Press, 2010), 119

[3] Ibid, 125

[4] Jeannine Fiedler, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, (London, UK: Phaidon Press Limited, 2001), 10.11

[5] Interview by Jimena Blazquez Abascal, in James Turrell, Fundacion NMAC (Milano: Edizioni Charta, 2009), 37